Effective Governance of Open Spatial Data (2016-2018)

This is a summary of the article ‘Vancauwenberghe, G., Valečkaitė, K., van Loenen, B. & Welle Donker, F. (2018). Assessing the Openness of Spatial Data Infrastructures: Towards a Map of Open SDI. International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructures Research, 13. The full article can be found here.

This paper introduced the Open Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI) Assessment Framework as a new approach for assessing the openness of SDIs. Open SDIs are SDIs in which non-government actors such as businesses, citizens, researchers and non-profit organizations can contribute to the development and implementation of the SDI, use spatial data with as few restrictions as possible and benefit from using these geographic data. A pilot application of the new framework resulted in the Map of Open SDI in Europe, which aimed to show the level of openness of national SDIs in Europe. The map could become a relevant and practical tool that shows the status of Open SDIs in Europe and supports decision makers and practitioners in making their own SDI more open.

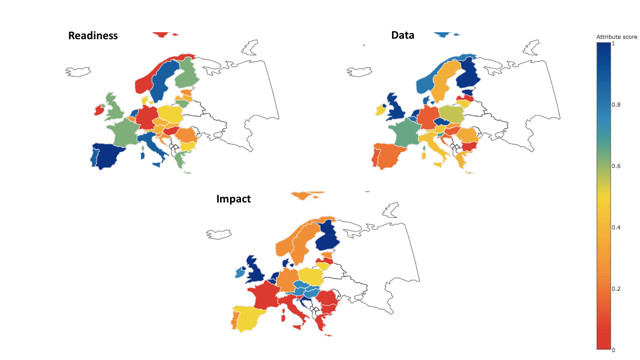

THe figure above shows the first prototype of the Map of Open SDI in Europe based on preliminary data as collected by students, which were afterwards validated by the authors of this paper. This resulted in a full overview of the 28 EU Member States as well as Norway. It should be noted that the prototype was only used to introduce the rationale and approach behind the Open SDI Assessment Framework, since the process of validating the data was still ongoing and the preliminary data contained some missing and incorrect values. The figure shows how the Open SDI Assessment Framework allows for the comparison of countries with respect to the openness of their SDI.

The figure shows three separate maps representing the Readiness, the Data and the Impact dimensions. The maps not only show the differences between countries, but also how the situation within one country can be different for these three dimensions. While in some countries, the national SDI can be considered to be open with respect to all three dimensions (e.g. Finland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom), other countries are doing especially well with respect to one single dimension (e.g. Estonia with its high score on the Data dimension).

In our Open SDI Assessment Framework, Readiness focuses on the development and implementation of the SDI, and assesses the extent to which non-government actors can participate in and contribute to developing and implementing the SDI. Non-government actors can be involved in both the governance and implementation of the SDI, and various instruments could support or enable this involvement: a national vision, a strategy on open geographic data, or on opening the SDI, a government-wide open data policy for all geographic data or a governance structure in which also non-government actors are represented. An open SDI also means that non-government actors could add their data to the SDI, thereby making it an infrastructure for sharing all types of geographic data, including government, business, citizen and research data.

The Data dimension of our framework deals with the availability and accessibility of geographic data to different types of users including businesses, citizens, nonprofit organizations and other users within and outside public administration. The Data dimension adds some other requirements to spatial data, in addition to more traditional requirements such as metadata availability, accessibility through discovery, and viewing and downloading services. Users should be able to easily find the data they need, via generic web search services or national data portals. Other important features or characteristics of data in an Open SDI can be derived from open government data principles and existing open data assessments: spatial data should be openly available to anyone, free of charge and openly licensed.

The Impact dimension focuses on the benefits of using geographic data for businesses, citizens, non-profit organizations and other actors. In order to realize these benefits, non-government actors should also use geographic data to make more informed decisions, to improve their existing processes, products and services, or to create new products or services. Benefits of using open spatial data include at least three main categories: increased transparency, public participation, economic growth and innovation, but also increased government efficiency and effectiveness.

This article was prepared in the context of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship project on the topic ‘Effective Governance of Open Spatial Data’ (2016-2018). The central research question the project aimed to answer was: what is the impact of different models for governing open spatial data on the performance of open spatial data policies in Europe? To answer this research question, several research activities were executed, including a case study of two countries that were among the leading open data countries in the world: the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.